(Mis)Communication with Sara Mesa's Un Amor

Review | Sara Mesa’s Un Amor (2024, tr. Katie Whittemore)

Living in a country where the language spoken is not my mother tongue, opportunities for miscommunication are abundant. Despite my proficiency in French, I still find myself in moments of incomprehension and misunderstanding. I am not a native speaker and, while my grasp of the language is (hopefully) always evolving, unfamiliar vocabulary, strong accents and fast spoken French can still sometimes make it seem like an entirely different language to the one I studied at university.

The concept of translation is ever-present in my day-to-day; my work simultaneously relies on English and French, forcing my brain use both at once. I often find myself involuntarily translating phrases in my head, one way or the other, by force of habit.

As an overthinker, word choice sometimes feels like an active decision, rather than a subconscious reflex. Will one verb be received as overly familiar, too formal, or suggestive? Understanding linguistic technicalities and intricacies often leaves me more inhibited, less sure of myself as I internally struggle for the best way to express myself, rather than just trusting my gut.

Translation is central to Sara Mesa’s Un Amor. Her protagonist, Nat, moves to the remote village of La Escapa to focus on a literary translation project. Instead, however, she finds herself entangled in the politics of rural life.

There is a brooding unease throughout Mesa’s text, embodied by the El Guaco mountain which looms over the village. Characters hide ulterior motives, conversations contain unspoken feelings and the community is governed by unwritten rules. The rural escape that Nat craved proves to be more confining than the life she fled.

Issues of translation in Un Amor are not limited to the written word however, nor even to communication between different languages. Mesa questions how human difference affects understanding amongst even those who share a language. In this broader sense, translation miscommunications arise between Nat and the rural community as she adapts to its customs and conventions, between Nat and her neighbour-turned-lover Andreas as their differing perspectives on the relationship ultimately lead to its breakdown, and even between Nat and herself as she struggles to reconcile her intentions, her actions and her reality.

The transactional nature of relationships complicates miscommunications within Un Amor. Andreas and Nat’s relationship begins with a proposal: he will fix her leaky roof for free, provided that she sleeps with him. Ultimately, Nat is unable to translate this inherently transactional relationship into an emotional one, without the willing participation of Andreas. Throughout the text, relationships are defined by a conflict between personal desire and duty to others. Even in her relationship with rescue dog, Sieso, Nat obtains trust and companionship in exchange for food and shelter.

Adapting the text into English, Katie Whittemore captures Mesa’s sharp and concise voice. It is not reliant on an overly literary or flamboyant style, but prioritises an astute and erudite simplicity. The process of translating Un Amor must have been particularly thought-provoking, given Nat’s own role and responsibilities as a translator.

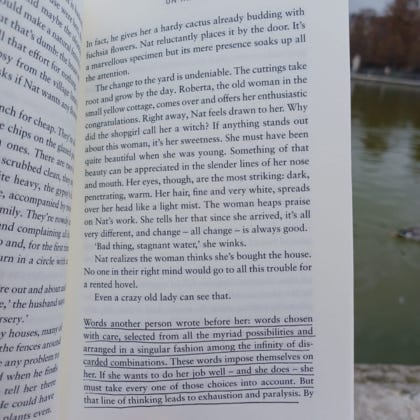

‘Words another person wrote before her: words chosen with care, selected from all the myriad possibilities and arranged in a singular fashion among the infinity of discarded combinations. These words impose themselves on her. If she wants to do her job well – and she does – she must take every one of those choices into account. But that line of thinking leads to exhaustion and paralysis.’ Sara Mesa, Un Amor

But the ‘exhaustion and paralysis’ that Nat experiences in relation to her professional work translates into her personal relationships too. Overanalysing the intentions and motivations of those around her feeds Nat’s paranoia, further isolating her from genuine human connection. Mesa exposes the cycle by which social isolation is maintained: fearing that the words spoken by her neighbours do not align with their internal thoughts, Nat too self-censors, hindering their open and honest communication.

Un Amor examines the barriers that prevent us from understanding each other fully; Mesa questions the ways that we close ourselves off to each other and enable miscommunication. Differences do not need to be overcome, but they must be understood. In Un Amor, difficulties arise when these differences become divisions, when weaknesses are exploited, and when exclusion replaces inclusion.

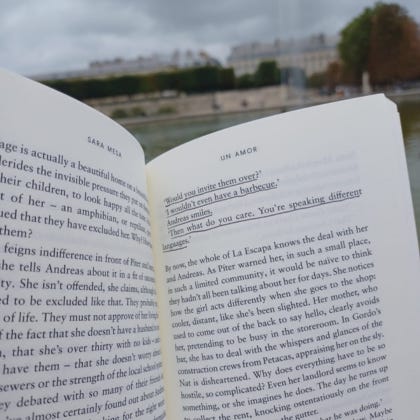

‘Would you invite them over?’

‘I wouldn’t even have a barbecue.’

Andreas smiles.

‘Then what do you care. You’re speaking different languages.’ Sara Mesa, Un Amor

Misunderstandings do not prevent me from speaking French. Instead, they help me to learn more about both the language and the culture within which I have immersed myself. When we open ourselves to new perspectives, differences do not disappear but enhance understandings of both ourselves and each other.

Interesting. I wonder what Derrida might have to add to this reflection on how we understand and misunderstand each other's language...